Introduction

For millennia, plants have played an essential nutritional role in sustaining human life. With regard to the traditional use of plants, the study of edible and nutraceutical plants is of particular importance, especially in terms of efforts to improve the biodiversity of global culinary culture and food safety (Sujarwoa & Caneva,2016). Wild plants, even after the advent of agriculture, have formed an important part of the human diet (Łuczaj & Szymański,2007). Wild edible plants contain small amounts of carbohydrates, fats, and, protein, but they are also rich in water, minerals, and vitamins. Many wild edible plants are beneficial to human health (Esiyok et al.,2004).

In terms of plant diversity, Turkey is one of the richest countries in the temperate climatic zone. Thus, the flora of Turkey comprises 8,796 species (excluding an additional 192 species from the East Aegean Islands), of which approximately 34% are endemic (Davis,1965–1985; Davis et al.,1988; Güner et al.,2000). An additional 945 species were added to the flora of Turkey with the publication of the last checklist (Özhatay et al.,2013). An increase in the diversity of plants naturally has an effect on their traditional use, and this, in turn, is reflected in the richness of Turkish culinary practices (Dogan,2012). Ethnobotanical studies conducted in Turkey have reported that 1,200 plant taxa are used as food (Ertuğ,2014).

Traditionally, Turkish people have used plants for medicinal purposes, as well as for food, fuel, dyes, garden ornamentals, agricultural tools, and furniture (Baytop,1999). Wild edible plants, in particular, are of great importance to the Turkish people owing to the handing down of traditions from one generation to the next (Dogan et al.,2004). In Turkey, the gathering of edible plants from the wild reflects the inadequacy of the country’s economy in previous years. As a consequence, local people, owing to social pressure, have generally preferred to conceal this practice lest they lose their social status. Thus, began a process of deliberately not acknowledging this aspect of their cultural heritage. However, in recent years there has been a revival in nature-orientated lifestyle preferences in Turkey, which has reversed this process. Likewise, there has been a renaissance in our interest in wild edible plants and what our grandparents taught us about them. This, in turn, has cultural implications (Ertuğ,2014). In recent years, the use of wild edible plants, especially in Turkish culinary practices, has become quite common. Such plants are consumed raw or cooked as vegetables and can be prepared in a number of ways, depending on the various regions of Turkey where they occur (Ertuğ,2014; Tan et al.,2017). A study conducted in the Aegean Region showed that as well as being a source of food and nutrients, wild edible plants also have the potential to provide an important source of income for local communities, especially if they are well managed (Tan et al.,2017).

Several recent studies have described the status of our current knowledge of the use of wild edible plants in Turkey (Ahıskalı et al.,2012; Alpınar,1999; Altundağ Çakır,2017; Arı et al.,2015; Bulut,2016; Dogan,2012; Dogan et al.,2004,2013,2015,2017; Duran et al.,2001; Ecevit Genç & Özhatay,2004,2006; Ertuğ,2004; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Esiyok et al.,2004; Gönüz et al.,2008; Kargıoğlu et al.,2008; Kızılarslan & Özhatay,2012; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2009; Polat & Satil,2010; Satıl et al.,2006,2008; Selvi et al.,2013; Tan et al.,2017; Uysal et al.,2010), but none of these studies have included Biga. Therefore, the goal of this study was to record the wild edible plants used as food, spice, and tea in Biga/Çanakkale to address this gap in our knowledge. To this end, information regarding the wild edible plants of Biga, such as their local names, methods of use, as well as the particular parts used, was recorded.

Material and Methods

Study Area

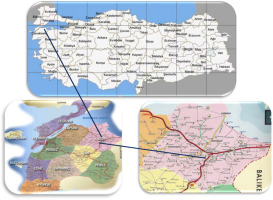

The study area of Biga, located in the southwestern part of the Marmara Region in Turkey, is the largest district of the Çanakkale Province (Figure 1). It is flanked by Gönen (Balıkesir) to the east, Lapseki (Çanakkale) to the west, Çan and Yenice (Çanakkale) to the south, and the Marmara Sea to the north. It covers an area of 1,331 km2 and comprises three municipalities and 108 villages (Figure 2). In 2018, the total population was 90,576 (http://www.nufusune.com/). The research area has a Mediterranean climate. According to the grid classification system for the Flora of Turkey, Biga is part of the Mediterranean plant geography region and falls within the A1(A) square (Davis,1965–1985). This region contains different types of vegetation (forest, maquis, and dune) (Akkaya,2008).

Biga has a varied cultural background as do many villages and the Turkish-origin population is mixed with immigrants from the Balkans and/or Caucasian (Yoruk, Muhacır, Bosnian, Pomak, Tatar, Circassian, Kumuk) immigrants since the Ottoman-Russian War (1877–1878). The resultant local culture is richly diverse, and this has an effect on the use of plants. As far as agriculture is concerned, mainly wheat, rice, sunflower, corn, legumes, some vegetables, and fruits are cultivated here (Gürsu,2001).

Field Study

This investigation forms part of an ethnobotanical study of Biga conducted between 2011 and 2014. In this study, information regarding wild plants, including their local names, the ways in which they are used, and the parts used, were recorded. Information concerning the wild edible plants of the region was compiled following several visits to the same villages. We interviewed a total of 165 people in Biga City and in its 49 associated villages. Interviews were conducted with people over 30 years old who had lived in the villages for more than 10 years. Of the informants, 119 were male and 46 were female. Their ages varied from 31 to 86, with a mean of 64 years. Information regarding edible plants was collected by means of face-to-face interviews (Figure 3). The informants were mainly farmers, shepherds, homemakers, a tradesman, chiefs of the villages, and retired individuals. Interviews were conducted at various localities, such as fields, gardens, village squares, village bazaars (markets), and coffeehouses. International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (International Society of Ethnobiology,2006) was strictly followed.

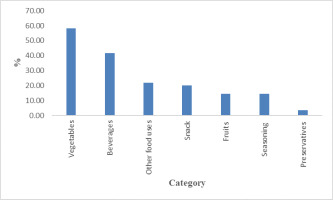

For this study, the obtained data were assigned to one of the following seven categories of edible plants based on folk knowledge: Vegetables – plants whose leaves and/or stems are eaten; fruits – plants whose fruits and/or seeds are consumed; beverages; seasoning or spices; preservatives – used to preserve dried fruit called “kak;” snacks – plants whose young shoots, stems, and/or roots are eaten raw or chewed; other food uses – plants not included in any of the above categories.

The plants were collected with the help of the informants. Collected plant samples were pressed, dried, and kept in a deep-freeze for 5–7 days at −28 °C in accordance with standard herbarium techniques. Taxonomical determinations of the collected specimens were made using the Flora of Turkey and the Aegean Islands (Davis,1965–1985; Davis et al.,1988; Güner et al.,2000). The voucher specimens are housed at the Herbarium of Faculty of Forestry, Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa (ISTO).

Data Analysis

The cultural important index (CI) (Parto de Santaya et al.,2007; Tardío & Parto de Santaya,2008) was calculated for each taxon according to the following formula:

The index was obtained by totaling the UR (use report) for every use category (i, varying from only one use to the total number of uses, NU) recorded for a given taxon divided by the number of informants interviewed in this study (N). This is a quantitative method that demonstrates the importance of the most commonly used species based on information provided by informants. The theoretical maximum value of the index is the total number of different use categories (NUs) (Tardío & Parto de Santaya,2008).

Results

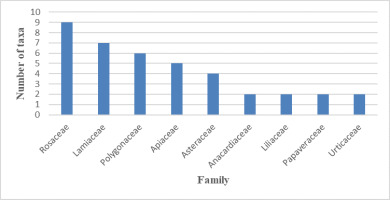

The study revealed that 55 plant taxa belonging to 41 genera were wild edibles. The wild edible plants of Biga are presented in Table 1 and arranged alphabetically according to their scientific names. These scientific names were verified for each of the species using The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org/), and popular names are shown in parentheses. The most frequently used plants were representatives of the families Rosaceae (16%), Lamiaceae (13%), Polygonaceae (11%), and Apiaceae (9%) (Figure 4). Additionally, in Biga, some of these plants were used for medicinal purposes. The genera containing the greatest number of edible plant taxa were Rumex (six taxa), Thymus, Eryngium, Mentha, Oenanthe, Papaver, Prunus, Rubus, and Urtica (each containing two taxa).

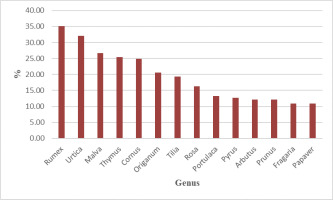

Genera, which are known to represent more than 10% of the plant population, in the study area were Rumex, Urtica, Malva, Thymus, Cornus, Origanum, Tilia, Rosa, Pyrus, Arbutus, and Prunus (Figure 5). The genus Rumex, at 35%, had the highest frequency, followed by Urtica (33%) and Malva (27%). Based on the calculated cultural importance index (CI) (Parto de Santaya et al.,2007; Tardío & Parto de Santaya,2008), U. urens and U. dioica had the highest values, whereas Platanus orientalis had the lowest.

In several cases (e.g., where different species from the same genus closely resembled each other, or members of the same genus occupied different areas), some taxa were known by the same local, vernacular name. For example, Oenanthe pimpinelloides and O. silaifolia are known as “Kazayağı,” Papaver rhoeas and P. dubium are known as “Gelincik,” Rubus canescens and R. sanctus are known as “Böğürtlen,” Rumex crispus, R. pulcher, and R. patientia are known as “Ekşilabadik, Ilıbada, Iştır, Labada,” R. tuberosus subsp. creticus, R. tuberosus, and R. acetosella are known as “Ekşi kulak,” “Kuzukulağı,” “Kuzukulak,” “Yeşil kulak,” Urtica dioica and U. urens are known as “Isırgan,” and Thymus thracicus and T. longicaulis are known as “Kekikotu,” “Taşkekiği, and “Yerkekiği” (Table 1).

Table 1

List of wild edible plants of Biga.

[ii] Previous ethnobotanical literature records: 1 – Ahıskalıet al. (2012); 2 – Alpınar (1999); 3 – Altundağ Çakır (2017); 4 – Arı et al. (2015); 5 – Bulut & Tuzlacı (2009); 6 – Bulut (2016); 7 – Cakilcioglu et al. (201)1; 8 – Dogan et al., (2004); 9 – Dogan (2012); 10 – Dogan et al. (2013); 11 – Doganet al. (2015); 12 – Dogan et al. (2017); 13 – Duran et al. (2001); 14 – Ecevit Genç & Özhatay (2004); 15 – Ecevit Genç & Özhatay (2006); 16 – Emre Bulut & Tuzlacı (2006); 17 – Ertuğ et al. (2004); 18 – Ertuğ (2004); 19 – Esiyok et al. (2004); 20 – Fujita et al. (1995); 21 – Gönüz et al. (2008); 22 – Han & Bulut (2015); 23 – Honda et al. (1996); 24 – Kargıoğlu et al. (2008); 25 – Kızılarslan & Özhatay (2012a); 26 – Kızılarslan & Özhatay (2012b); 27 – Koçyiğit & Özhatay (2006); 28 – Koçyiğit & Özhatay (2009); 29 – Polat & Satil (2010); 30 – Polat & Satil (2012); 31 – Satıl et al. (2006); 32 – Satıl et al. (2008); 33 – Selvi et al. (2013); 34 – Sezik et al. (1991); 35 – Sezik et al. (1997); 36 – Sezik et al. (2001); 37 – Tan et al. (2017); 38 – Tuzlacı & Aymaz (2001); 39 – Tuzlacı & Emre Bulut (2007); 40 – Uysal et al. (2008); 41 – Uysal et al. (2010); 42 – Uysal et al. (2012); 43 – Uzun et al. (2004); 44 – Yeşilada et al. (1993); 45 – Yeşilada et al. (1995); 46 – Yeşilada et al. (1999); 47 – Yücel & Tülükoğlu (2000).

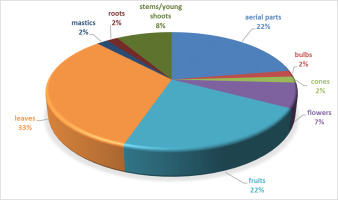

The edible parts of plants included leaves, aerial parts, young stems, bulbs, flowers, fruit, cones, and roots (Figure 6). The parts used the most were leaves (33%), aerial parts and fruit (22%), stems/young shoots (8%), and flowers (7%). Leaves are generally prepared for use by boiling, and are eaten as a salad, cooked as a meal, or used for pastry.

According to our data, wild edible plants were mostly eaten as vegetables (by 58% of the region’s population). Others were consumed as beverages (40%) or in other ways (22%) (Figure 7). The detailed results for each category are given below.

Vegetables

Thirty-two wild plant taxa were allocated to this category. Leaves or aerial parts of these plants were mostly consumed either raw or as cooked vegetables. Salads were commonly prepared, especially when plants were eaten raw. Plants used in fresh salads included: Anethum graveolens, Melissa officinalis, Mentha sp., Oenanthe sp., Rumex sp., and Stellaria media. Only Urtica species were preferred boiled for salads. The most frequently used genera used as cooked vegetables were Urtica, Malva, Portulaca, and Papaver. Different methods of preparation, such as boiling, roasting, or rolling (sarma in Turkish) were used. Onions, rice, or eggs could be added when cooking plants to add variety to the food. Also, plants are sautéed in oil and may be added to pastries. In Biga, leaves of Malva sylvestris and Trachystemon orientalis were consumed as rolled “sarma.” Traditional ovens, such as those that occur in gardens, continued to be used for cooking. Sometimes, it was preferable to bury certain parts of plants in ash, such as bulbs of Tulipa orphanidea, prior to cooking (Figure 8A–C).

Fruits

Seven wild plant taxa were assigned to this category. In Biga, consumption of fresh fruits of Cornus mas, Arbutus unedo, Fragaria vesca, and Rubus sp. was very common. Some fruits were prepared by drying and were stored for winter consumption. These were called “kak.” The dried fruit of both wild and cultivated pears was used in Biga.

Beverages

Beverages were usually prepared as herbal tea, fruit juice or drinks prepared by boiling fruit with sugar. Twenty-three wild plant taxa were assigned to this category. Fifteen taxa were currently being used as herbal tea and prepared as an infusion. Plants for which the aerial parts were used for herbal teas included: M. officinalis, Mentha longifolia subsp. typhoides, M. pulegium, Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, T. thracicus, T. longicaulis, U. dioica, and U. urens (Figure 8D,E). Leaves of Laurus nobilis, flowers of Hypericum perforatum, Lavandula stoechas, Matricaria chamomilla, and Tilia tomentosa, and fruit of Rosa canina were also used for herbal teas. Platanus orientalis leaves were mixed with black tea and consumed as a beverage at breakfast.

Two different methods were preferred for preparing beverages by boiling fruit with sugar. The first used dried fruits and was called “dried fruit compote” (hoşaf in Turkish), whereas the second used fresh fruit and was called “compote” (komposto in Turkish). These were often consumed at mealtimes. The fruit juice prepared from Vitis vinifera fruit was called “koruk” and consumed as a refreshing drink during summer.

Seasoning or Spices

The aerial parts of eight wild plant taxa (A. graveolens, L. nobilis, O. vulgare subsp. hirtum, Rhus coriaria, M. longifolia subsp. typhoides, M. pulegium, T. longicaulis, and T. thracicus) were allocated to this category. These spice plants were added fresh to salads or cucumber-yogurt (cacık in Turkish), and dried parts were used to give flavor to dishes. In particular, Origanum, Mentha, and Thymus species were harvested mainly during spring and subsequently dried for winter use (Figure 8D).

Preservatives

Aerial parts of O. vulgare subsp. hirtum were used to preserve stored, dried fruit (kak in Turkish) for winter use. To make kak, the sliced, dried fruit was dipped into the liquid in which the plants had been boiled, and immediately removed. The kak fruit was then left to dry in readiness for use in winter.

Snacks

Local people, especially when out walking, consumed certain plant parts (leaves, young shoots, fruit, peeled stems, and roots) as fresh snacks. These included: Asparagus acutifolius, Chenopodium album, Crateagus monogyna, V. vinifera, Eryngium sp., and Rumex sp. Freshly gathered leaves and young shoots could sometimes be used in cooking. Besides these, the mastic of Pinus brutia was chewed as a snack.

Other Food Uses

Foods, such as pickles (lacto-fermentation was a common and traditional form of pickling in the area), marmalade, jam, molasses (pekmez in Turkish), and “tarhana” (the Turkish name for a soup unique to Anatolia), which were widely consumed in the study area, were assigned to this category. Aerial parts of O. vulgare subsp. hirtum were added to “tarhana” for flavor. Generally, cultivated plants were used in preparing these foods, but additionally, 11 wild plant taxa were employed in the region for this purpose, especially A. unedo, F. vesca, C. mas, R. canina, Prunus sp., and Rubus sp. Pickles were prepared from P. elaeagnifolia fruit, and the pickle juice was also consumed (Figure 8F).

Plants of the genera Origanum, Anethum, Malva, Mentha, Portulaca, Rosa, Rubus, Rumex, Tilia, and Urtica were collected from the wild and sold in Biga at the local bazaar (Figure 9).

Discussion

In Turkey, it is known that wild plants are preferred as food, especially by people living in rural areas (Ertuğ,2014). The use of 55 wild plants as food in our study area can be considered indicative of the continuation of traditional knowledge in the region.

A comparison of this study with previous edible plant studies (Ahıskalı et al.,2012; Alpınar,1999; Altundağ Çakır,2017; Arı et al.,Arı et al. (2015); Bulut,2016; Dogan,2012; Dogan et al.,2004,2013,2015,2017; Duran et al.,2001; Ecevit Genç & Özhatay,2004,2006; Ertuğ,2004; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Esiyok et al.,2004; Gönüz et al.,2008; Kargıoğlu et al.,2008; Kızılarslan & Özhatay,2012; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2009; Polat & Satil,2010; Satıl et al.,2006,2008; Selvi et al.,2013; Tan et al.,2017; Uysal et al.,2010) and other ethnobotanical studies (Bulut & Tuzlacı,2009; Cakilcioglu et al.,2011; Emre Bulut & Tuzlacı,2006; Fujita et al.,1995; Han & Bulut,2015; Honda et al.,1996; Kızılarslan & Özhatay,2012; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2006; Polat & Satil,2012; Sezik et al.,1991,1997,2001; Tuzlacı & Aymaz,2001; Tuzlacı & Emre, Bulut2007; Uysal et al.,2008,2010,2012; Uzun et al.,2004; Yeşilada et al.1993,1995,1999; Yücel & Tülükoğlu,2000) is presented in Table 1. Some of the species identified in our study area, according to other studies, are used for purposes other than food, such as medicinal (M), animal fodder (FD), dye (D), and ornamental (O) uses, demonstrating the ethnobotanical importance of these plants in Turkey. Malva sylvestris, P. rhoeas, R. canina, and R. acetosella (species which we showed are used as food in Biga) are also recorded as food plants in 25 of the studies that we used for comparative purposes (Ahıskalı et al.,2012; Alpınar,1999; Altundağ Çakır,2017; Arı et al.,2015; Bulut,2016; Dogan,2012; Dogan et al.,2004,2013,2015,2017 Duran et al.,2001; Ecevit Genç & Özhatay,2006; Emre Bulut & Tuzlacı,2006; Ertuğ,2004; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Kargıoğlu et al.,2008; Kızılarslan & Özhatay,2012; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2009; Polat & Satil,2010,2012; Satıl et al.,2006,2008; Selvi et al.,2013; Tan et al.,2017; Uysal et al.,2008,2010; Yücel & Tülükoğlu,2000). In Biga and its vicinity, the use of these wild species is quite common. Based on these results, it can be concluded that these species are commonly used as food in Turkey. Furthermore, these species are widely distributed in Turkey (Babaç,2004); thus, facilitating their widespread use as food. Similarly, A. unedo, Portulaca oleracea, S. media, O. pimpinelloides, R. coriaria, Rumex, and Urtica species, taxa which we showed in previous studies were used as food, were also well known and commonly used for this purpose in Biga. A comparison with previous studies revealed that the use of some taxa as food (e.g., H. perforatum, L. nobilis, O. silaifolia, P. orientalis, R. tuberosus subsp. creticus, Sorbus domestica, Taraxacum aleppicum, Thymus thracicus, and Tulipa orphanidea) occurs only in Biga and its vicinity.

The consumption of certain species, such as H. perforatum and L. stoechas, used as a tea for medicinal purposes are very common in the region, but it was shown that a small number of people also consumed these species daily in the form of beverages. The medicinal use of both of these plant taxa is widespread in Turkey (Alpınar,1999; Arı et al.,2015; Cakilcioglu et al.,2011; Ecevit Genç & Özhatay,2006; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Honda et al.,1996; Kızılarslan & Özhatay,2012; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2006; Polat & Satil,2010; Selvi et al.,2013; Sezik et al.,2001; Tuzlacı & Aymaz,2001; Tuzlacı & Emre Bulut,2007; Uysal et al.,2008,2010,2012; Uzun et al.,2004; Yeşilada et al.1993,1995). For example, L. stoechas is brewed together with sage and lime to form a tea that is drunk by a small number of people. Similarly, although not common, P. orientalis leaves are mixed with black tea to form a beverage that is drunk at breakfast.

The use of L. nobilis leaves as tea was reported by only one informant. This species is usually used as a spice in our country (Alpınar,1999; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Koçyiğit & Özhatay,2009; Satıl et al.,2006), and this is also true of the study area. Asparagus acutifolius is consumed only as a fresh snack in the study area but is usually eaten cooked or roasted in Turkey (Bulut,2016; Dogan,2012; Polat & Satil,2010).

Some edible plants are collected from the wild and sold in the bazaars of Biga. These are popular and include Origanum, Anethum, Malva, Mentha, Portulaca, Rosa, Rubus, Rumex, Tilia, and Urtica species. Moreover, some (e.g., Anethum and Mentha) are also grown in gardens, demonstrating that they are used frequently, unlike those which are only occasionally used and thus, purchased, as required, from bazaars. However, whenever P. oleracea is consumed, it is preferable to collect it from the wild, because the wild species is tastier and has better properties. The consumption of P. oleracea is quite common in Turkey (Alpınar,1999; Arı et al.,2015; Dogan,2012; Dogan et al.,2004,2013; Ertuğ,2004; Ertuğ et al.,2004; Kargıoğlu et al.,2008; Polat & Satil,2010; Satıl et al.,2006; Uysal et al.,2010). By contrast, R. coriaria is often purchased and consumed as a spice, rather than being collected from the wild. Dogan et al. (2013) reported that the genera Origanum, Anethum, Malva, Portulaca, Rumex, and Urtica are sold in the local markets of Izmir. Origanum onites and R. canina are also sold in the local markets of Balıkesir (Selvi et al.,2013), whereas Origanum, Malva, Rumex, and Urtica species are collected for commercial purposes and also sold in the markets of Balıkesir (Polat & Satil,2010; Satıl et al.,2008). The fact that natural food plants are sold at local markets indicates that they are an important priority food. Urtica is also commonly used, and it is widely believed by the population that it must be eaten at least once a year by every household for health purposes.

The use of thyme is also very common in the region. People usually buy thyme from sellers of medicinal herbs, the “aktar,” but O. vulgare (known as “Baharat otu,” “Güveotu,” “Güveci,” “Kekikotu,” “Keklikotu,” “Koru çayı,” “Uzunkekik,” “Yabankekiği”) is also collected from the wild. In addition to the use of O. vulgare as a spice, it is also made into a tea and is widely used as a preservative for the storage of dried fruit for use in winter.

For centuries, Anatolian people have used every kind of edible leaf to make sarma (which in Turkish means “wrapping” and involves the rolling or wrapping of vegetable leaves around ingredients) (Aras,2013; Dogan et al.,2015). In Biga, M. sylvestris and T. orientalis leaves are eaten as sarma, and records show that they are also eaten in this form in various other regions of Turkey (Dogan et al.,2015,2017; Tuzlacı,2011).

Pickling is known to be a fairly important practice for preparing foods for the winter. Cultivated vegetables are preferred for this purpose. However, in Biga and its vicinity, the consumption of pickle juice prepared from the wild species Pyrus elaeagnifolia is common. Records show that this species is eaten as a pickle in different regions of Turkey (Kargıoğlu et al.,2008; Sõukand et al.,2015; Tuzlacı,2011; Uysal et al.,2010).

It is claimed by some sources that certain food plants identified by us for the area are also used in other regions of Europe (Benítez et al.,2017; Biscotti & Pieroni,2015; Dénes et al.,2012; Dolina & Łuczaj,2014; Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013,2015; Nedelcheva et al.,2017). Species shown by these studies to be consumed cooked or as a salad include the following; Amaranthus sp. (Dolina & Łuczaj,2014; Nedelcheva et al.,2017), A. acutifolius (Biscotti & Pieroni,2015; Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013), C. album (Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013,2015), M. sylvestris (Nedelcheva et al.,2017), P. rhoeas (Benítez et al.,2017; Biscotti & Pieroni,2015; Dénes et al.,2012; Dolina & Łuczaj,2014; Łuczaj et al.,2013), P. oleracea (Biscotti & Pieroni,2015; Dénes et al.,2012; Dolina et al.,2016), Urtica sp. (Benítez et al.,2017; Biscotti & Pieroni,2015; Dénes et al.,2012; Dolina & Łuczaj,2014; Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013,2015; Nedelcheva et al.,2017), R. acetosella (Dénes et al.,2012; Łuczaj et al.,2015; Nedelcheva et al.,2017), R. patientia (Dénes et al.,2012), and R. pulcher (Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013,2015), and these results closely resemble our own findings. Species whose fruit are shown to be consumed either raw or as jam by these same studies include: A. unedo). Once again, these plants were used in the same way in Biga and its vicinity.

It was determined that some genera, regardless of species, were used for the same purpose in the study area. For example, all species of Oenanthe, Papaver, Rumex, and Urtica were used as food. Fruits of Rubus were consumed raw or made into jam, marmalade, or compote. Species of Thymus and Mentha were used as a spice or for making herbal tea. Similarly, in some studies, it was shown that the genera Papaver, Rumex, and Urtica, regardless of species, are used as food (Alpınar,1999; Dogan,2012; Dogan et al.,2004; Emre Bulut & Tuzlacı,2006).

The findings common to our study and those conducted in Europe can be explained in terms of species distribution. Furthermore, the use of similar species as food may be caused by the cultural proximity of the regions, or to the widespread intercultural sharing of information. Similarities between the local names used for the plants in the villages occupied by the Balkan immigrants of Biga and those used in the Balkans support this hypothesis. Sevgi et al. (2018) showed that in Biga, 283 plant names are used for 142 traditionally used wild taxa. Cornus mas, which is known as “Drenka” in the villages of Biga occupied by Balkan immigrants, is variously called “Dren,” “Drenka,” “Drenjula,” “Drenjulvić,” “Drenulika,” “Drenutka” (Dolina et al.,2016), “Drenjina,” “Drjen” (Dolina & Łuczaj,2014), and “Drinina,” “Drinjina,” “Dren” (Łuczaj et al.,2013) in the Balkans. Urtica urens is known as “Kupriva” in Biga, and remarkably, U. dioica is known as “Kopriva” (Dolina & Łuczaj,2014; Dolina et al.,2016; Łuczaj et al.,2013) and “Kopresh” (Nedelcheva et al.,2017) in the Balkans. Urtica dioica and U. urens are generally known to the public by the same vernacular names. Crateagus monogyna, which is known as “Gogiç” in Biga, is called “Glog cerveni,” “Glogovići,” “Glogoviki,” “Glogujka” (Dolina et al.,2016) in the Balkans. The vernacular names “Kruşka” and “Krusha” are given to P. elaeagnifolia and Pyrus sp., respectively (Nedelcheva et al.,2017). Additionally, the names “Dibje kruškice,” “Divlja kruška” (Dolina et al.,2016), and “Divlja kruška” (Łuczaj et al.,2013) are given to P. amygdaliformis, and therefore represent the genus Pyrus in general. Nedelcheva et. al. (2017) reported that Rubus, Rumex, and Thymus have the same vernacular names, “Kapina,” “Labada,” and “Keklik otu.” These names are identical to those used in Biga. Likewise, Łuczaj et al. (2013) reported that R. ulmifolius is known as “Kupina,” whereas we showed that in Biga, R. sanctus is known as “Kapina.” Again, this demonstrates that members of the genus Rubus have been given the same vernacular name, regardless of species.

Conclusions

People in Turkey, and worldwide, are again discovering the health benefits of using wild edible plants for cooking; thus, helping to maintain the correct balance between mental, spiritual, and physical health. For this reason, the identification of traditionally used edible plants has become very important.

In this study, the wild edible plants of Biga/Çanakkale were recorded for the first time. Our results showed that even in districts located close to cities, the use of wild edible plants still persists. Documenting the traditional culinary use of these plants, before the information is lost forever, is now paramount.